Still defrosting from my visit to Washington DC, I’ve reflected on the conference that I’ve just attended in complexity, inequalities and health. Sound complex? Well, here’s a simple summary that’s not as snow-covered as I have been over the past few days. But why waste your coffee time reading this article? Well, this might give you some insights about the perspectives and methods emerging from leading researchers working in complex systems, health and inequalities, as well as the investments in the area from the main health policy agency in the US.

- “Complex Systems, Health Disparities & Population Health: Building bridges”

http://conferences.thehillgroup.com/UMich/complexity-disparities-populationhealth/agenda.html This conference was organised by the USA’s Network on Inequalities, Complexity and Health (NICH) and hosted by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) on campus in Bethesda, Maryland, USA. Not much tweeting throughout the two days, but I did start a hashtag that was picked up: #NICHconference

- The socio-ecological model of health lives on

As with most quality public health conferences, we saw the socio-ecological model in the opening comments. And one of the authors of papers about the socio-ecological model was present! It is a crucial framework by which we think, talk, measure, and report – important to communicate the individual, interpersonal, organisational, community and social policy impacts upon health of populations globally. It shows the complexity of health determinants, simply.

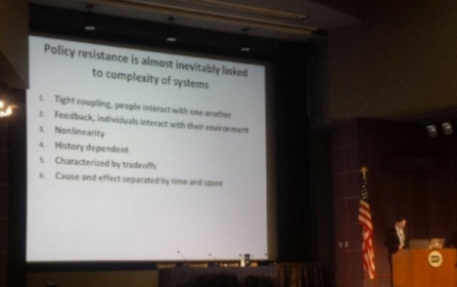

- Complex systems theory challenges our thinking about how health is constructed

To begin we heard the nuts and bolts of complex systems science as it applies to health, and a message that the “find it, fix it” approach to public health isn’t working. If traditional approaches were effective, we wouldn’t have epidemics of non-communicable disease and unfair health inequalities. Unbalanced investment exists in most contexts – for example in the USA they know that 40% of health problems are socially determined, 50% behavioural and only 10% due to health care. However, only 3% is spent on societal and individual-level prevention strategies (complex solutions), whilst 97% is spent on health care (simple solutions).

- Complex systems science reorients our thinking about how to act to improve health

We can always interrogate the ‘why’ of health issues and inequalities. A person smokes because it’s socially acceptable, affordable, possible to do where they live, work/learn and play, and because cigarettes are available– actively marketed by for-profit companies. Food supply was given as another example. The production, marketing, acquisition, distribution, retail, purchasing and consumption of food is dynamic and depends on many factors such as market forces, housing, economics and built environment. Consider that the majority of countries in the world have McDonalds in urban areas; and, that the majority of countries have 50% of their population housed in urban areas. What influences do these factors have on healthy food supply and access? Then how does that affect health and lifespan? As you can see, it’s complex. Check out this paper by Sandro Galea for more: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3134519/

- Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler

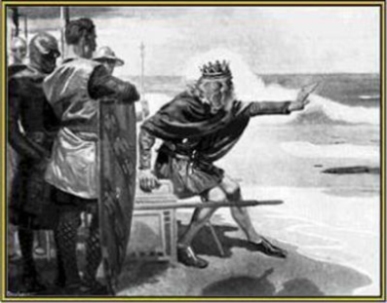

One speaker articulated that using simple interventions to address complex health issues is likely to fail. It’s a bit like King Canute ‘ordering back the tide’ – with health interventions and measurements, we can’t simply push against how things go naturally in a system, we need to identify multiple points and levers for interventions at different socio-ecological levels. Similarly, intervention research in this area can’t continue to be ‘linear’ and use averages for estimating effects –we need to capture heterogeneity. It’s tempting and logical to believe that if the parts get better (e.g. risk factors) then the whole will get better (e.g. populations), but change is contextually dependent. The response to multiple interventions will be very different than the totality of responses to each intervention separately. In other words, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts!

Image from: http://canute2.sealevelrise.info/slr/Story%20of%20Canute

- When it’s all ‘too complex’, or when there’s no ‘real’ data?

Try simulating or modelling data! There are often times when observed health issues are ‘too hard’ to disentangle from the modifiers and contextual factors. Modelling epidemiological associations between factor X (e.g. fast food) and factor Y (e.g. heart disease) may not reveal the nuances of what produced the issue in the first place – the causes of the causes. The same goes for evaluating multifaceted interventions across the many socio-ecological levels – it’s hard to measure each and every factor that might have had an impact upon the observed outcomes, and then to attribute causation. Thus, we are often without empirical data that integrates the diversity of elements in a system, so it’s hard to prove what determinants to target. Also, limited quality evidence exists on processes and effectiveness of complex interventions, so we’re often ‘working in the gaps’. Synthetic estimates can be produced by building simulation models, guided by existing data, evidence and theory. Models can control experimental conditions in a complex system, which is obviously impossible to do in ‘real world’ observational studies. Also, and rather compellingly, we heard that standard statistical approaches can’t examine feedback and adaptive mechanisms between environments and individuals/agents – whereas computational modelling can. This recent paper by Amy Auchincloss et al provides a recent example, with links between neighbourhood resources and obesity under study: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/oby.20255/full

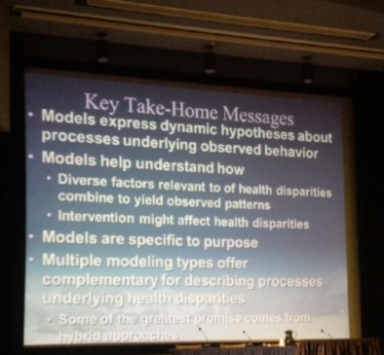

- Methods for research of complex systems, health determinants and impacts

The main methods presented in the presentations and posters included system dynamics, social network analysis (SNA), agent based modelling (ABM), and discrete event modelling. These methods, having emerged from complex systems science, are being applied to public health research. The methods were described as tools to help us make sense of the interactions within complex systems, and the impacts that interventions might have on health and inequalities. For a primer, see the take-home messages from Nathan Osgood below, refer to a recent paper by Doug Luke and Katherine Stamatakis – these sources will be eminently better than my interpretation would be! http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3644212/pdf/nihms414057.pdf

- What are some of the applications for simulation and modelling research?

For the most part, the presentations and posters highlighted a series of examples of modelling research studies that explored a range of factors related to health inequalities at the individual, institutional and neighbourhood level. Mostly, this provided case studies for how inequalities are produced, but some focused on estimating potential effects of interventions.

- Examples of data simulation/modelling studies

At the individual and community level, an ABM explored differential effects of alcohol outlet density restrictions and policing upon alcohol-related violence and homicide among white Americans and African-Americans. A simulation study explored potential effects of upstream policy on Healthy eating and Physical activity, finding proof of concept that it may be more effective to target neighbourhood factors, not race, in reducing disparities in some contexts. At the population level, a case study from New Zealand was described, conducted when the earthquakes in 2011 interrupted the annual census, and modelled data was used to predict ongoing trends in primary health care access among Maori and Pacific Islander populations.

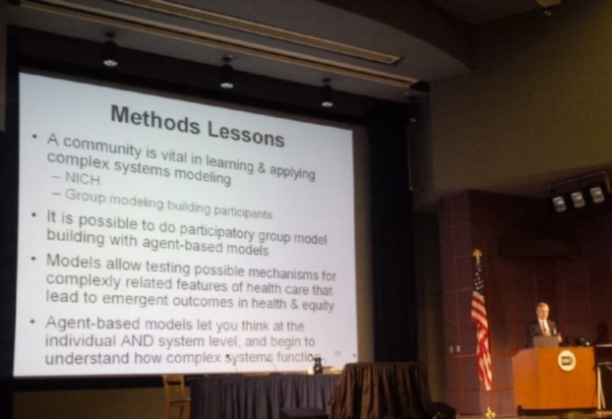

- Progress and pitfalls for complex systems methods in public health

Collectively, from this conference it seems that certain systems science methods may tell us more about the nuanced factors causing health inequalities. It may also help reveal leverage points and suggest how to tailor interventions. But as with all research, challenges and limitations remain with these methods. These studies require interdisciplinary teams to ensure sufficient expertise in epidemiology, mathematics, computer programming, geography, public health and urban planning. Working together is essential –from observational research to computational modelling, the first step is a doozy!

Another challenge highlighted was that ultimately, we need to be able to link the models to ‘real’ data, to ensure their validity. Involvement of community stakeholders and decision-makers in the process was discussed only briefly, but this would appear to be a key step in verifying models. Community physician and systems scientist Kurt Stange described a great example of a participatory process of community stakeholder involvement in model planning and development. This may be a good point for us to start, to ensure that we ‘keep it real’.

- Closing thoughts from a complexity novice

From a KTE perspective, I would think that external validity would be a key challenge for the application of this research, which may be difficult to reconcile. The conference left me pondering how do we use the evidence generated for decision-making? How can we be sure that modelled data reflects what’s in the ‘real world’? A discussion on using these models to guide policy was led by Complex dynamics researcher Ross Hammond, and NIH program director Stephen Marcus, which began to raise these questions. I would imagine, as for research evidence generated through ‘traditional’ methods, that a similar approach to knowledge translation and exchange would be required for evidence generated through modelling.

So after that, a penny for your thoughts? Leave a comment if you’re using/exploring these methods!

Written by Dr Tahna Pettman

Research fellow: Public Health Evidence and Knolwedge translation

Evaluation fellow: CO-OPS collaboration

The Jack Brockhoff Child Health & Wellbeing Program.

The University of Melbourne

e: tpettman@unimelb.edu.au